This is part two of a two-part series. I value Stockman's opinion particularly because he is a partner in a Private Equity firm. They know what makes business and free enterprise tick better than any other group of people in the world.

GREENWICH, Conn. (MarketWatch) — The destructive result of the Federal Reserve’s earlier housing and consumer credit bubble became the excuse for embracing a destructive zero interest rate policy which is self-evidently fueling even more destruction.

This destruction is namely, the exploitation of middle class savers; the current severe food and energy squeeze on lower income households; the illusion in Washington that Uncle Sam can comfortably manage $14 trillion in debt because the interest carry is close enough to zero for government purposes; and the next round of bursting bubbles building up among the risk asset classes.

Moreover, the Fed soldiers on with its serial bubble-making, even though it is evident that the hallowed doctrines of modern monetary theory and the inherently dubious math of Taylor rules have failed completely.

Indeed, the evidence that the Fed no longer has any clue about the transmission pathways which connect the base money it is emitting with reckless abandon (e.g. Federal Reserve credit) to the millions of everyday pricing, hiring, investing and financing outcomes on Main Street sits right on its own balance sheet. Specifically, if the Fed actually knew how to thread the needle to the real economy with printing press money it wouldn’t have needed to manufacture $1 trillion in excess bank reserves — indolent entries on its own books for which it is now paying interest.

So in the present circumstances, ZIRP and QE2 amount to a monetary Hail Mary. There is no monetary tradition whatsoever that says the way back to U.S. economic health and sustainable growth is through herding Grandma into junk bonds and speculators into the Russell 2000 (NASDAQ:RUT) .

Admittedly, the junk-bond financed dividends being currently extracted by the LBO kings from their debt-freighted portfolios may enable them to hire some additional household help and perhaps spur some new jobs at posh restaurants, too. Likewise, the 10% of the population which owns 80% of the financial assets may use their stock market winnings to stimulate some additional hiring at tony shopping malls.

That chairman Bernanke himself has explained in so many words this miracle of speculative GDP levitation, however, does not make it so. The fact is, if transitory wealth effects add to current consumer spending, they can just as readily subtract on the occasion of the next “risk-off” stampede to the downside. Indeed, the proof — if any is needed — that cheap money fueled asset inflations do not bring sustainable prosperity lies in the still smoldering ruins of the U.S. housing boom.

In truth, the Fed’s current money printing spree has no analytical foundation, and amounts to seat-of-the-pants pursuit of a will-o’-wisp — the idea of a perpetual bull market. Like the Bank of Japan, the Fed has made itself hostage to the global speculative classes, and must repeatedly inject new forms of stimulus to keep the bubbles rising.

This is the only possible explanation for its preposterous decision to allow the big banks to resume dissipating their meager capital accounts by paying “normalized” dividends and by resuming large-scale stock buybacks. These are the same financial institutions that allegedly nearly brought the global economy to its knees in September 2008, according to the Fed chairman’s own words.

In what is no longer secret testimony to the FCIC (Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission), Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke claimed that the Wall Street meltdown “was the worst financial crisis in global history” and that “out of maybe 13…..of the most important financial institutions in the United States, 12 were at risk of failure within a period of a week or two”.

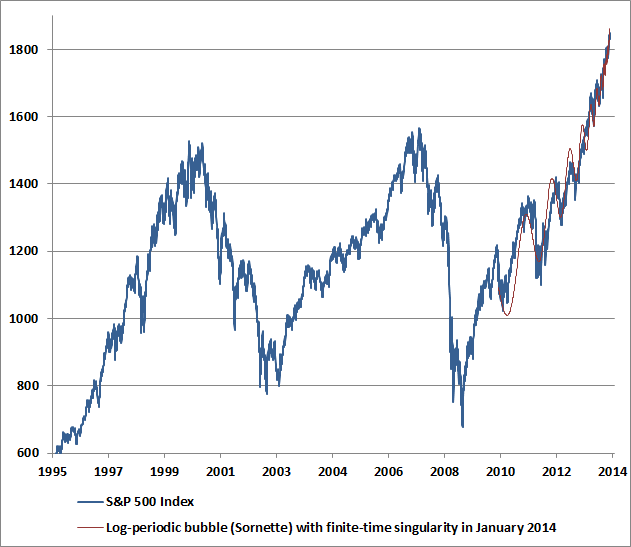

That testimony was recorded just 15 months ago, but the financially seismic events it references have apparently already faded into the dustbin of history. Still, even if the dubious proposition that the banking system has fully healed were true, what did the Fed hope to accomplish besides goosing the S&P 500 (CME:INDEX:SPX) via speculative rotation into the bank indices?

Well, there are no other plausible explanations. Certainly the stated theory — namely, that by green lighting disgorgements of capital today the Fed’s action will facilitate bank capital raising and new lending in the future —merits a loud guffaw. The fast money has already priced in whatever dividend increases and share buybacks may occur before the next banking crisis, but the last thing these speculators expects is a new round of dilutive capital issuance by the banks. Stated differently, the bid for bank stocks unleashed by the Fed’s relief action is predicated on speculators’ pocketing any near-term “surplus” capital, not leaving it in harms way.

Moreover, even if the Fed’s action had the effect of bolstering, not depleting, bank capital the larger issue is why does our already massively bloated banking system need more capital in any event? The reflexive answer is that this will help restart the flow of credit to Main Street, but it doesn’t take much digging to see that this is a complete non-starter.

The household sector is still saddled with massive excess debt — unless you believe that the credit bubble of recent years is the sustainable norm. The fact is, prior to the Fed’s easy money induced national LBO, debt-to-income ratios at today’s levels were unthinkable. In 1975, for example, total household debt—including mortgages, credit cards, auto loans and bingo wagers—was about $730 billion or 45% of GDP

During the 1980’s, however, this long-standing household leverage ratio began a parabolic climb, and never looked back. By the bubble peak in Q4 2007, total household debt had reached $13.8 trillion and was 96% of GDP. Yet after 36 months of the Great Recession wring-out, the dial has hardly moved: household debt outstanding in Q4 2010 was still $13.4 trillion, meaning that it has shrunk by the grand sum or 3% (entirely due to defaults) and still remains at 90% of GDP or double the leverage ratio that existed prior to the debt binge of the past three decades.

So the banking system does not need more capital in order to increase credit extensions to the household sector. In fact, the two principal categories of household debt — mortgage loans and revolving credit, continue to decline as American families slowly shed unsupportable debt. The only reason total household debt appears to be stabilizing in recent quarters is that student loan volumes are soaring, but this growth is being funded entirely by the Bank of Uncle Sam now that private bank loan guarantees have been eliminated.

Indeed, the startling fact is that the approximate $1 trillion of student loans outstanding — sub-prime credits by definition — now exceed the $830 billion of total credit card debt by a wide margin. While this latest student loan bubble will end no better than the earlier credit bubbles, the larger fact remains that the household sector is only in the early stages of deleveraging. Not the least of the self-evident motivating forces here is that the leading edge of the household sector — the 78 million strong baby boom generation — appears to be figuring out that it is not 1975 anymore, and that retirement and old age are approaching at a gallop.

This obvious household deleveraging trend remains a mystery to the Fed and to the Wall Street stock peddlers who occasionally moonlight as economists. One recent air ball offered up by the latter is that the ratio of debt to disposable personal income (DPI) has dropped materially, and that this proves the household sector has been healed financially and is ready to borrow again. Specifically, the household debt-to-DPI ratio has fallen to 116% from a peak of 130% in late 2007.

Never mind that this measure of household financial health stood at just 62% back during the healthier climes of 1975. It is evident that even the modest improvement in this ratio during the last three years is a statistical illusion. It turns out that the debt-to-DPI ratio is improving mainly because the denominator has gained about $885 billion or 8.3% since the end of 2007.

Yet this gain in DPI has nothing whatsoever to do with an improved debt carrying capacity in the household sector. Thanks to the more or less continuous riot of Keynesian stimulus in Washington since early 2008, we have had a tax holiday and a transfer payment bonanza. Specifically, in the three years since the fourth quarter 2007 peak, personal taxes are down at a $312 billion annual rate (which adds to DPI, an after-tax measure) and transfer payments are up by a $572 billion annual rate.

Both of these are components of DPI, and taken together ($884 billion) they account, quite astoundingly, for 99.8% of the DPI gain since Q4 2007. Moreover, it does not take a lot of figuring to see that these trends won’t last. The Federal tax take is now less than 15% of GDP — the lowest level since 1950 — and will be rising year-after-year in the decade ahead, as will personal tax burdens at the state and local level.

At the same time, the 30% surge in transfer payments over the last three years is mostly done. Unemployment insurance payments — which accounted for much of the rise — will be flat or shrinking in the near future, and various one-time low income programs have already expired. Moreover, the bulk of the current $2.3 trillion in transfer payments go to elderly and poverty level households which carry negligible portions of the $13.4 trillion in household debt, in any event.

By contrast, the ratio of household debt to private wage and salary income — a far better measure of debt carrying capacity — has not improved at all. Household debt amounted to 255% of private wage and salary income at the peak of the credit boom in late 2007, and was still 251% in Q4 2010. At the end of the day, the household debt-to-DPI ratio improved solely because Uncle Sam went on a borrowing spree and temporarily juiced DPI with tax abatements and transfer handouts.

In short, banks don’t need more capital to support household credit because the latter is still shrinking, and will be for a long time to come. Moreover, it might as well be said in this same vein that the business sector doesn’t need no more stinking debt, neither!

At the end of 2005 — before the credit bubble reached its apogee — the non-financial business sector (both corporate and non-corporate entities) had total credit market debt of $8.3 trillion, according to the Fed’s flow of funds data. By the end of 2007, this total had soared by 25% to $10.4 trillion. But contrary to endless data fiddling by Wall Street economists, the business sector as a whole has not deleveraged one bit since the financial crisis. As of year-end 2010, business debt was up a further $500 billion to $10.9 trillion.

The whole propaganda campaign about the business sector becoming financially flush rests on an entirely spurious factoid with respect to balance sheet cash. Yes, that number is up a tad — from $2.56 trillion in fourth quarter 2007 to $2.86 trillion at the end of 2010. Still, this endlessly trumpeted gain in cash balances of $300 billion is more than offset by the far larger gain in business sector debt — meaning that, on balance, the alleged cash nest egg held by American business is simply borrowed money.

At the end of the day, $10.9 trillion is a lot of debt in absolute terms, but based on the Fed’s data on the market value of business sector assets, it is also crystal clear that the relative burden of business debt has been rising, not falling. At the bubble peak in late 2007, business sector assets were valued at $41.5 trillion but alas this figure had shrunk to $36.9 trillion by the end of last year. The grim reaper of real estate deflation has done its work in the business sector, too.

Consequently, total business debt now amounts to 29.4% of business assets---a considerable rise from the 25.2% ratio at the bubble peak in late 2007. What the bullish cheerleaders of recovery constantly forget is that in an epochal deflation like the present one, debts remain at their contractual amounts, even as asset values wither.

So the real question regarding the Fed’s green light for bank dividends and buybacks is quite clear. Banks don’t need more capital to make new loans to households and business. What they actually need is to preserve their current artificially bloated retained earnings accounts in order to protect the taxpayers from the next — virtually certain — banking meltdown.

In this light, the Fed’s action is especially meretricious. If it weren’t in such a hurry to juice the stock market and thereby keep the illusion of recovery going, it might have considered extending the regulatory sequester on bank capital for a few more quarters or even years — thereby preserving a shield for the taxpayers until it has been demonstrated by the passage of time, not by the passing of phony stress tests, that the American banking system is truly out of the woods.

After all, the bottled-up profits currently alleged to be resident in the banking system have not been expropriated by the Fed; they have just been temporarily sequestered — a condition these wards of the state should gladly endure in return for continued access to taxpayer backed deposit insurance and the Fed’s borrowing widow, as well as their license to engage in the lucrative business of fractional reserve banking. Indeed, the fast money should be as capable of pricing in any “excess” capital in the banking system, as it has already been in goosing bank stocks in anticipation of higher profit distributions.

And it is here where the historical data on Bernanke’s 12 out of 13 crashing financial dominoes essentially speaks its own cautionary tale. At the peak of the credit and housing boom in 2006, these 13 most important financial institutions booked $110 billion of net income, and disgorged more than $40 billion of that amount in dividends and stock buybacks.

Would that these fulsome profits and attendant distributions had been real and sustainable, but the historical facts inform otherwise. By 2007, the groups’ profits had dropped to $64 billion, and then in 2008, the 10 institutions which survived to year-end reported a staggering loss of $56 billion. Moreover, if the massive loses incurred by the terrible three — Washington Mutual (NYSE:JPM) , Wachovia (NYSE:WFC) and Lehman — during their final, unreported stub quarter is added to the tally, losses for the year would approach $80 billion.

The unassailable truth here is that in 2006 and 2007 the banks were disgorging phantom profits to their shareholders. When the crunch came in 2008, bank capital had been badly depleted by these unwarranted dividends and stock buybacks.

The danger, of course, was buried in the balance sheets all along. Back in their 2006 heyday, the top 13 financial institutions had $10.2 trillion of total assets — and a not inconsiderable portion of that figure was worth far less than book value, as ensuing events proved. Today the nine banks which are the survivors and assigns of these 13 institutions still have $10.1 trillion in asset footings — hardly a measurable reduction despite the goodly amount of write-offs which have been taken in the interim.

The Fed’s foolish wager — and it is foolish because there is no real purpose other than a momentary boost to bank shares — is that this once toxic asset ridden $10 trillion balance sheet is now squeaky clean. Yet why would any sane observer embrace that dubious proposition?

While the banks have been relieved of mark-to-market accounting, they are still knee-deep in the very asset classes whose ultimate recoverable value remains exposed to the real estate meltdown. Residential housing prices are now clearly in the midst of a double dip, and rates of new construction and existing unit sales are spilling off the bottom of the historical charts

Still, the banking system holds $2.5 trillion of residential mortgages and home equity lines — plus $350 billion of construction loans and more than a trillion of mortgage backed securities. Maybe they have enough reserves to cover the remaining sins in this $4 trillion kettle of residential debt, but betting on housing bottom has been a widow-maker for several years now — and there is nothing on the horizon to suggest that this epochal bust will not make a few more.

Likewise, the banking system is carrying $1 trillion of commercial real estate loans, and the open secret is that “extend and pretend” refinancing is the primary underpinning of current book values. Similarly, the Fed has rigged the steepest yield curve in modern times, but it is a fair bet that as it is gradually forced to normalize interest rates, current record net interest margins will be squeezed. And it is also probable that some of the $2.7 trillion of government, corporate and other securities owned by the banking system may be worth less than par in a world where money rates are more than zero.

In short, a banking system that by the lights of the Fed was on the verge of extinction just 28 months ago could not possibly have gotten well in the interim. In shades of 2006, the nine survivors did report net income of $54 billion in the year just ended, and it is these retained earnings that have purportedly brought bank capital ratios to the pink of health. Then again, the cynic might wonder whether the trading book and yield curve profits of 2010 might not disappear as fast as did the mortgage origination, securitization and trading profits of 2006-2007.

One thing is certain, however, and that is that these behemoths are now truly too big to fail. At the end of 2006, the asset footings of the Big Six — J.P. Morgan, Bank of America (NYSE:BAC) , Wells Faro (NYSE:WFC) , Citigroup (NYSE:C) , Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS) and Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS) — were $7.1 trillion. Saving the system through shotgun marriages in the interim, our financial overloads have permitted the group to grow its assets by 30% to $9.2 trillion.

If you believe that these massive financial conglomerates are a clear and present danger to the American economy, you might opine that they are too big to exist, as well. But even from a more quotidian angle — unless you are in the banking index for a trade — it’s pretty easy to see that so-called banking profits should have remained under regulatory sequester for a few more economic seasons, at least.

David Stockman is a former member of the House of Representatives and a member of the Reagan administration. He currently owns his private equity fund, Heartland Industrial Partners, L.P .