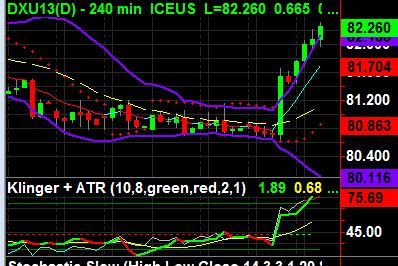

Unfortunately, we are seeing the soon arrival of both food price hyperinflation coupled with the destruction of the value of the US dollar, as depicted in these two charts. The first depicts the devaluation of the US Dollar over the past several weeks, and the second chart shows the latest update of the price of corn and other food commodities.

Saturday, May 8, 2021

Monday, November 18, 2019

Dollar Devastation

"Following the report that Trump and Powell discussed negative rates, among other things, the dollar has slumped to session lows, with the Bloomberg dollar index dipping below 1,200." Zero Hedge

Tuesday, September 6, 2016

Thursday, December 3, 2015

Thursday, June 20, 2013

Monday, January 16, 2012

As Markets Become Unravelled

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Monday, August 15, 2011

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

Monday, August 8, 2011

Three Scenarios of the Relationship Between the Dollar and the Stock Market

by Charles Hugh Smith from the Of Two Minds blog:

The Stock Market and the Dollar: There Are Only Three Possibilities

With stocks and the dollar on a see-saw, there are only three possibilities to choose from.

Since the stock market is in the news (perhaps as a result of trillions of dollars/euros/yen/yuan/quatloos having suddenly vanished from millions of accounts), it seems timely to examine the key correlation between stocks and the U.S. dollar. As I have often noted here, this "big picture" correlation is a simple see-saw: when the dollar is scraping bottom, stocks are at their highs, and when the dollar is up then stocks are tanking.

At the risk of alienating chart-averse readers, I've marked up the charts of the S&P 500 (SPX) and the U.S. dollar index (DXY).

For those who aren't going to look at the charts, what they suggest is that there are really only three possibilities in play:

A. Stocks go up and the dollar drops to new lows

B. Stocks fall and the dollar rises significantly, a pattern that has repeated several times since 2007

C. The see-saw breaks and stocks and the USD rise or fall together.

The key to the relationship between stock valuations and the dollar is corporate profits. When the dollar declines, then U.S. global corporations' overseas earnings--now roughly 60% of total profits for many big global corporations--expand as if by magic when stated in dollars.

When the euro and the dollar were equal back in the early 2000s, then 100 euros of profit was $100 when stated in dollars. When the euro rose to $1.60, then the same 100 euros of profit earned by the U.S. corporation in Europe became a stupendous $160 in profit when stated in dollars.

This explains why the Fed has been so keen to trash the dollar: it magically increases corporate profits and thus drives stocks higher. The mainstream financial media's explanation for the weak-dollar policy is that the Fed is anxious to increase exports, but this is a sideshow; exports make up less than 9% of the U.S. GDP. The real action is in corporate profits, which thanks to the weak dollar are near all-time highs of almost 14% of the entire GDP.

So those picking #3, the see-saw breaks and the dollar and stocks rise or fall in parallel, have to explain why this dynamic has broken down, and describe the new dynamic which has caused the USD and SPX to rise or fall as one.

Those picking #1, that stocks are about to rebound and the dollar will plunge to new lows, have to explain what force will drive stocks higher and weaken the dollar. The easy answer is the Fed will launch a "monetary easing" a.k.a. QE3 to goose risk assets, including stocks.

Perhaps this will do the trick, but just on a purely technical basis, the stock market has a number of arrows in its back, and nobody knows just yet if any of them are poisoned:

There are a lot of arrows in the back of the market. One of the biggest is declining volume; if volume is the weapon of the Bull, then declining volume has a distinctly bearish implication. One of the basic tenets of technical analysis is support/resistance: key levels (often round numbers like 1,200 or 12,000) become important when stocks bounce off them (support) or are unable to punch through them (resistance). When stocks break support, then that line becomes resistance when stocks try to rise. If stocks break through resistance, then that line become support should markets decline.

When key support levels are decisively broken, huge damage is done to the market, even if the actual point drop appears modest. The SPX broke a key support level just above the pyschological line at 1,200. This has provided strong support/resistance going back to 2008, so it's meaningful.

In the typical course of things, the SPX will attempt to break above that resistance on a rebound off the strong support offered by the 200-week moving average, a level it almost kissed last week.

But there are a lot of other arrows which suggest that will be difficult. Chartists like to draw trendlines, and if we trace out all the trendlines from the 2009 bottom, we get a fan of broken trendlines. This suggests a weakening major trend.

Then there's those three indicators arrows firmly planted in the market's back; RSI (relative strength), MACD (moving average convergence-divergence) and stochastics are all diverging from the rally--all have been declining as the SPX traced out a classic three-peak "head and shoulders" topping pattern over the past few months.

If we look at RSI, we see it is not yet oversold. We also see that when things get ugly, as they did in late 2008, the RSI can actually climb out of being oversold even while the market is in a freefall. When markets are falling, RSI can remain low for months.

MACD offers a very simple window into stock trends: MACD above the neutral line, Bullish, MACD below the neutral line, Bearish. MACD is heading straight for the neutral line and if it crashes through it, it is a distinctly negative indicator.

Stochastics can stumble along an oversold bottom for months, too, so there is little evidence here of an impending rally.

There is strong support around the 1,050 mark, but the market sliced through this like a hot knife through butter back in 2008 before finding some solid ground around 900. When that failed, 666 marked the final trough.

Maybe the SPX recovers the 1,220 level, maybe not. Nobody knows how many of the arrows in its back are poisoned. We'll just have to watch support/resistance.

Those picking #2, a rise in the dollar and a corresponding drop in stocks, have to explain how the dollar can survive the poisoned chalice proffered by the Federal Reserve. The Fed's entire game plan boils down to driving the dollar down by whatever means are necessary. Many observers see the Fed as all-powerful, irresistable, with god-like powers to move markets.

But as I have noted here many times, the Fed's mighty armament is revealed as a BB gun when compared to the foreign exchange markets ($2-3 trillion traded daily), the global risk trade ($30-$100 trillion, depending on what markets you include), and global debt denominated in dollars (in the trillions).

Thus the Fed's power is not the infamous printing press, but the belief of market players that the Fed can single-handedly reverse markets. On a large enough scale, the Fed does have some leverage; for example, the Fed played some $18 trillion into global markets to save the day in 2008.

It is my contention that the Fed's political capital and credibility--the "magic" of omnipotence--have both sunk below critical thresholds (Don't Fight Bet On The Fed August 5, 2011) and that the law of diminishing returns has emasculated the market-moving value of QE3, 4, 5, etc.: each infusion to goose the risk trade does less than the previous prop job.

The timeline of manipulation has also compressed: the Fed's "save" in 2007 lasted a year, the order-of-magnitude greater "save" in 2008-9 bought perhaps a year and a half, and QE2 boosted risk assets for less than a year. If QE3 is smaller than QE2, then its effects will be entirely transitory--weeks, perhaps only days or even hours.

Dollar Bears are assuming the USD will crash through support to new lows. That is certainly one possibility--but it can only happen if stocks rise (choice #1) or the see-saw breaks (#3).

The indicators are exhibiting positive divergence, i.e. slowly rising even as price declines or noodles around a narrow trading range. The USD has traced a classic pennant or flag "wedge" of lower highs and higher lows. This compression of price action often leads to a big move up or down. Those betting on the Fed's omnipotence to crush the dollar to new lows have to overlook the positive divergence and the previous pattern of the dollar rising dramatically when the risk trade unravels. Those betting the dollar will repeat that pattern have an easier case to make technically.

From a fundamental view, the DXY index is on a see-saw with the Euro, as the DXY is composed of a basket of six currencies dominated by the Euro (Euro 57.6%, Yen 13.6%, Sterling 11.9%, Canadian Dollar 9.1%, Swedish Krona 4.2%, and Swiss Franc 3.6%).

Thus those betting on the DXY hitting new lows are implicitly betting on a recovery of the Euro. THose betting on major dollar bounce are betting that the Euro is in deeper trouble than the U.S. dollar.

There is no crystal ball that foretells the future; when it comes to forecasting the future, we have only charts, judgment, intuition and probabilities.

Wednesday, July 27, 2011

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Friday, July 8, 2011

Friday, May 20, 2011

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Imagine a country that spends and prints trillions to patch up any problem.

Now imagine another country where there is no central Treasury, meaning that bail-outs are less easy, and which has a central bank that has mopped up liquidity over the past year, rather than engage in quantitative easing.

Why does it surprise anyone that the latter, the eurozone, has a stronger currency than the former, the US? Because of peripheral countries’ debt refinancing issues? And the potential for contagion? These are real and serious issues, but in our assessment, they should be primarily priced into the spreads of eurozone bonds, not the euro itself.

Think of it this way: in the US, Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke has testified that going off the gold standard during the Great Depression helped the US recover faster than other countries. Fast-forward to today: we believe Bernanke embraces a weaker currency as a monetary policy tool to help address the current state of the US economy. What many overlook is that someone must be on the other side of that trade: today it is the eurozone, which is experiencing a strong currency, despite the many challenges in the 17-nation bloc.

A year ago, the euro appeared to be the only asset traded as a hedge against, or to profit from, all things wrong in the eurozone. This was partly driven by liquidity, because it is easier to sell the euro than to short debt of peripheral eurozone countries; and as the trade worked, others piled in. As the euro approached lows of $1.18 against the dollar, the trade was no longer a “safe” one-way bet and traders had to look elsewhere. As a result, the euro is now substantially stronger, yet peripheral bond debt is much weaker.

The one language policymakers understand is that of the bond market. A “wonderful dialogue” has been playing out, encouraging policymakers to engage in real reform. Often minority governments have made extremely tough decisions. Ultimately, it us up to each country to implement their respective reforms; political realities will cause many to fall short of promises, resulting in more bond market “encouragement”. Policymakers hate this dialogue, of course, but must respect it.

Any country may default on its debt. The problem is that it may be impossible to receive another loan, at least at palatable financing costs. Any country considering a default must be willing and able to absorb the consequences, which is an overnight eradication of the primary deficit.

That’s why it is in Greece’s interest to postpone any debt restructuring until more reform has been implemented.

The risk/reward consideration of a default is likely to be more favourable a few years from now. The banking system has already had time to prepare for a Greek default, among others, unloading securities to the European Central Bank. Politics may cause an earlier default, but Greece would be shooting itself in the foot, as an important incentive for further reform through the carrot and stick approach of the European Union and International Monetary Fund is taken away. Moreover, why refuse the easy money?

Debt reduction in principle is certainly possible. Belgium in the 1990s had a debt to gross domestic product ratio of about 130 per cent and has since taken it down to about 98 per cent. The Belgium caretaker government appears easily capable of continuing the country’s prudent fiscal path.

Portugal’s main challenge is that it is a small country with a weak government, but it is capable of living up to its commitments.

Spain is a major country that has had a housing bust – nothing new in modern history. Given Spain’s low total debt to GDP and an assertive approach to overhauling its banking system, we sometimes compare Spain to Finland. In the early 1990s, Finland had a housing bust, as trade with the Soviet Union ended, followed by a banking system implosion and soaring unemployment. Both Finland then and Spain now have low debt-to-GDP ratios. It may be easier to implement reform in Finland (and Finland had a free-floating currency), but Spain has a real economy and ample resources.

Ireland is trickier, because a default may be an attractive political consideration. However, we would be more concerned about fallout to sterling, given the exposure of the British banking system, than the euro.

In the US, the day investors come to accept the reality that inflation, rather than fiscal discipline, is the path of least political resistance may be the day the bond market won’t be as forgiving. Unlike the eurozone, where consumers stopped spending and started saving a decade ago, the highly indebted US consumer may not be able to stomach higher interest rates. The large US current account deficit also makes the dollar more vulnerable to a misbehaving bond market than the eurozone.

In the medium term, we are far more concerned about risks to the US dollar than those posed by the Greek drama to the euro.

Axel Merk is president and chief investment officer of Merk Investments