Friday, June 19, 2020

Stock Bubble Continues It's Rise

Thursday, June 27, 2019

Farm Economy Getting Bludgeoned This Year

Zero Hedge this morning has this photo and article:

Todd Burrus, owner, said:

“If we experienced a year like this, I don’t remember it. When the farm economy is tough, it’s going to be tough for all the suppliers.”

Tuesday, June 4, 2019

Farm Production Weak

"The 12 month period that concluded at the end of April was the wettest 12 month period in U.S. history, and more storms just kept on coming throughout the month of May," said Michael Snyder today.

Bloomberg said yesterday, "There has never been a spring planting season like this one.

Rivers topped their banks. Levees were breached. Fields filled with

water and mud. And it kept raining."

Monday, May 20, 2019

Will Food Inflation Leap This Year?

"Mired by a rainy and chilly spring, U.S. farmers may soon give up on planting corn in rain-soaked parts of the Farm Belt because it is getting too late for money-making yields, said economist Scott Irwin of the University of Illinois. “I truly believe we are in ‘black swan’ territory as far as late corn planting is concerned,” he said over the weekend, using a term popularized during the financial crisis a decade ago."

The US Department of Agriculture reported last week that only 30% of U.S. corn acres were planted as of May 12; that's the fourth-slowest in records back to 1980 -- way behind the five-year average of 67%.

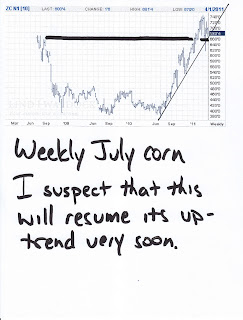

But perhaps there's still hope for a good crop this year. Reuters also had this:

"Rain-driven planting delays for U.S. corn have been dragged out long enough to cause a noticeable rally in Chicago-traded futures, but speculators were not yet ready to shed their enormously bearish positions as of early last week."

Wednesday, May 2, 2012

CME Expands Hours for Ag Futures

from Farm Futures:

CME Group announced Tuesday it would

expand electronic trading hours in its CBOT grain and oilseed futures

and options beginning Monday, May 14. The expansion will give the market

access to CBOT corn, soybeans, wheat, soybean meal, soybean oil, oats

and rough rice futures and options on CME Globex for 22 hours per day.

In a press statement, Tim Andriessen,

managing director, agricultural commodities and alternative investments,

CME Group says: "As we've grown our customer base in agricultural

commodities around the globe, we've received increased interest in

expanding market access by providing longer trading hours. In

particular, customers are looking to manage their price risk in our

deep, liquid markets during market moving events like USDA crop reports.

In response to customer feedback, we're expanding trading hours for our

grain and oilseed products to ensure customers have even greater access

to these effective price discovery tools."

Sunday to Monday - 5 p.m. to 4 p.m.

Monday to Friday - 6 p.m. to 4 p.m.

Open outcry trading hours will continue to operate from 9:30 a.m. to 1:15 p.m. Central time Monday to Friday.

Wednesday, April 6, 2011

UN Report Reveals New Record Food Prices

(Reuters) - Global food prices measured by the U.N.'s food agency may have come off record highs in March after falls in grain prices, but supply concerns and soaring oil prices mean such a move could just be a pause before new peaks.

The United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) on Thursday publishes its monthly Food Price Index, which measures price changes for a basket of cereals, oilseeds, dairy, meat and sugar.

The index hit a record high in February for a second straight month, passing peaks seen in 2008 during a food crisis which sparked riots and panic buying in places as far apart as Haiti, Cameroon and Egypt.

The FAO warned last month that fresh oil price spikes and stockpiling by importers keen to avert popular unrest would rock already volatile grain markets and food prices would remain close to record highs until new crop conditions are known.

World wheat and corn prices fell in the first three weeks of March to levels well below 2008 peaks amid political turmoil in north Africa and the Middle East and natural disaster in Japan, before starting to recover at the end of March.

Benchmark U.S. wheat futures lost about 3 percent for the month of March, while corn futures fell 4 percent, but both have been rising since the start of April on the back of persistent concerns about tight supplies and bad weather.

Strong demand for grains and vegetable oils from biofuels industry is also seen by FAO and other analysts as a driving force for food price rises, despite expected increases in planted areas this year.

Soaring oil prices are also adding to food product costs.

Oil prices on Wednesday rose to their highest since August 2008, driven by unrest in the Middle East and North Africa and dollar weakness ahead of an expected European Central Bank interest rate rise on Thursday.

Wednesday, March 30, 2011

Ag Commodity Inflation Is Here and Going to Get Worse

from Along the Watchtower blog:

Longtime readers will recall that we've had several conversations here regarding the impact that the Fed's quantitative easing policy is having on the costs of everyday food items. Soaring prices of agricultural commodities are going to continue to have a devastating effect on the purchasing power of average Americans and consumers around the globe. Since prices have now recovered some from the selloffs after the Japanese earthquake and tsunami and since there is no end in sight to QE, I thought it was time to once again take a look at out favorite commodities and assess where their prices may be headed over the spring and summer.

Let's start with the grains because rising grain prices cause all sorts of inflation. Not only are grains the raw input to countless consumer goods, grains are also the primary foodstuff for cattle ranchers and hog finishers as they prepare their herds for slaughter. Let's start with wheat, which is being influenced not just by the falling dollar. Price is also feeling the impact of the ongoing drought in the "winter wheat zone" of the high plains of Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-03-24/worst-texas-drought-in-44-years-eroding-wheat-beef-supply-as-food-rallies.html

Now take a look at the chart. Long-term support held at $7.50 and wheat looks almost certain to catapult higher very soon.

Now here's the deal with corn...it's expensive to grow! The primary fertilizer that Midwestern corn farmers utilize is anhydrous ammonia. Last year, anhydrous ammonia cost your average farmer about $425/ton. This year, the cost has almost doubled to $750-800/ton. So, while it might be tempting to seed a lot of acres with corn to capitalize on the high price, the input and production costs are so high that many farmers will choose to plant soybeans, instead. Less acres of corn planted lead directly to less production. Less production leads directly to even higher prices. (Remember that below when we get to cattle.)

So what about soybeans? Soybeans are the one grain that I don't expect to rise in price. They will, most likely, stay rangebound through the summer. Why? Besides the fertilizer costs affecting plantings, soybeans get extra acreage for another reason: Weather. Because soybeans have a shorter growing season, they are a "fall back plan" for many farmers who struggled to get corn planted due to overly wet spring conditions.

http://www.galesburg.com/news/x1777821638/Galesburgs-spring-outlook-cool-and-wet

If the upper Midwest spring turns out cool and wet, many farmers will forego corn planting and turn, instead, to soybeans. Extra supply = Lower cost.

Now, let's get back to corn. Have you ever heard the term "corn-fed beef"? Most of the best steakhouses proudly champion corn-fed beef because, frankly, its tastes a helluva lot better than grass-fed. The high sugar content of the corn gets converted into fat. The fat makes its way into the muscle and you, Mr. Steakeater, get yourself a beautiful, marbled "prime" steak. Fat cows are also desirable at slaughter because, well, they weigh more and cattle are sold by the pound. OK, so now, pretend for a moment that you're a cattle rancher. As your cattle are growing and being prepared for market (the term is "finished"), you want to feed them as much corn as they'll eat and you can afford. Corn at $7.00/bushel really cramps your business plan. Your first reaction is to control costs by thinning your herd, i.e. you sell some prematurely, before they are "finished". You might also simply want to sell some of your herd to take advantage of today's high prices.

http://www.saljournal.com/news/story/Cattle-prices-32411

Either way, this extra supply in the short term has actually worked to keep cattle prices from soaring at the same rate as the grains. But this is temporary. By this summer, supply will decrease as cattle that would have been coming to market just then have already been slaughtered. Are we already beginning to see this play out on the chart? Well, take a look:

Monday, March 14, 2011

Japan's Earthquake and Tsunami Disasters and Their Impact on Commodity Markets

from Agrimoney.com:

Sunday, March 6, 2011

Tuesday, January 11, 2011

More EPA Overreach

The American Farm Bureau Federation has filed a lawsuit in federal court to halt the Environmental Protection Agency's pollution regulatory plan for the Chesapeake Bay. AFBF says the agency is overreaching by establishing a Total Maximum Daily Load or so-called "pollution diet" for the 64,000 square mile area, regardless of cost. The TMDL dictates how much nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment can be allowed into the Bay and its tributaries from different areas and sources.

According to Farm Bureau, the rule unlawfully "micromanages" state actions and the activities of farmers, homeowners and businesses. EPA's plan imposes specific pollutant allocations on activities such as farming and homebuilding, sometimes down to the level of individual farms. Farm Bureau contends the Clean Water Act requires a process that allows states to decide how to improve water quality.

Also, Farm Bureau says EPA's TMDL is based on inaccurate assumptions. Farm Bureau President Bob Stallman says there is a basic level of scientific validity that the public expects and that the law requires. That scientific validity is missing here, and the impact could starve farming and jobs out of the region.

And finally, Farm Bureau believes EPA violated a requirement to allow meaningful public participation on new rules. The suit alleges that EPA failed to provide the public with critical information about the basis for the TMDL and allowed insufficient time for the public to comment.

Wednesday, January 5, 2011

Record World Food Prices

A combine harvester working in a wheat field.

That surge in food prices was aggravated by a rise in other commodities such as oil but the price spike was short-lived, with prices pulling back by the following season as the world economy tumbled and farmers increased grain plantings on a vast scale.

The FAO’s sugar index rose 6.7% on the month and also hit a record high in December of 398.4, according to the data going back to 1990. The index last hit a record high in January 2010.

Sugar prices have climbed to around 30-year highs due to strong demand fand low inventories around the world.

The FAO’s oils price index also jumped, rising 8.1% to 263 in December from 243.3 in November, while the cereals price index climbed 6.4% to 237.6 from 223.3.

Month-on-month increases in the FAO’s price indexes for meat and dairy were more muted — 0.5% and 0.3%, respectively. Still, the meat price index hit a record high of 142.2 in December 2010.

Food Inflation Is Here, and Going to Get Worse

For the first time since 2008, inflation is hitting consumers in the stomach.

Grocery prices grew by more than 1 1/2 times the overall rate of inflation this year, outpaced only by costs of transportation and medical care, according to numbers released Wednesday by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Economists predict that this is only the beginning. Fueled by the higher costs of wheat, sugar, corn, soybeans and energy, shoppers could see as much as a 4 percent increase at the supermarket checkout next year.

"I noticed just this month that my grocery bill for the same old stuff - cereal, eggs, milk, orange juice, peanut butter, bread - spiked $25," said Sue Perry, deputy editor of ShopSmart magazine, a nonprofit publication from Consumer Reports. "It was a bit of sticker shock."

While overall inflation nationwide was 1.1 percent, grocery prices went up 1.7 percent nationally and 1.3 percent in the Bay Area, said Todd Johnson, an economist for the Bureau of Labor Statistics office in San Francisco. "The largest effects on grocery prices here over the last month were tomatoes, followed by eggs, fish and seafood."

Produce steady

Across the country, the price of produce has remained fairly steady. But the U.S. Department of Agriculture predicts that next year the price of fruits and vegetables, like many other food commodities, could go up. The government agency is forecasting a 2 to 3 percent food inflation rate in 2011 - a pace that is not unusual in a rebounding economy."We usually err on the conservative side," said Ephraim Leibtag, a senior economist with the USDA, adding that "2011 holds a bit of uncertainty, so I wouldn't be surprised if it goes higher. If it goes to 6 percent, then we should be worried."

Michael Swanson, an agricultural economist at Wells Fargo, said that as long as corn, soybean and energy prices continue to climb, food inflation could reach 4 percent in 2011.

"The USDA always plays it safe," he said, adding that the nation is likely to see the biggest increases since 2008, when the food inflation rate was a record 5.5 percent.

The global demand for corn - used for food and ethanol - has swelled so much that feed costs for farmers and ranchers are being passed on to the consumer, Swanson said.

Gas, diesel play a role

Gas and diesel prices also are playing a role. Wheat costs went through the roof this year when 20 percent of Russia's crop was destroyed by drought and wildfires, causing the country, the third-largest producer in the world, to ban exports of the grain. The price of sugar, also used for ethanol in parts of the world, is priced at a two-decade high.Kraft Foods Inc., one of the world's largest food producers, has already announced plans to increase its prices because of mounting ingredient costs and flagging sales. General Mills, maker of everything from flour and baking mixes to cereal and Yoplait yogurt, has said it, too, will raise some of its product prices in January. Experts said consumers can expect the same from Kellogg's and Nestle.

"Food is a high-frequency driver," he said. "So if stores like Walmart and Kmart want to get shoppers in the door, it's to their benefit to keep prices low."

Thursday, November 18, 2010

UN Report Cites Skyrocketing Food Prices

The bill for global food imports will top $1,000bn this year for the second time ever, putting the world “dangerously close” to a new food crisis, the United Nations said.

The warning by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation adds to fears about rising inflation in emerging countries from China to India. “Prices are dangerously close to the levels of 2007-08,” said Abdolreza Abbassian, an economist at the FAO.

The FAO painted a worrying outlook in its twice-yearly Food Outlook on Wednesday, warning that the world should “be prepared” for even higher prices next year. It said it was crucial for farmers to “expand substantially” production, particularly of corn and wheat in 2011-12 to meet expected demand and rebuild world reserves.

But the FAO said the production response may be limited as rising food prices had made other crops, from sugar to soyabean and cotton, attractive to grow.

“This could limit individual crop production responses to levels that would be insufficient to alleviate market tightness. Against this backdrop, consumers may have little choice but to pay higher prices for their food,” it said.

The agency raised its forecast for the global bill for food to $1,026bn this year, up nearly 15 per cent from 2009 and within a whisker of an all-time high of $1,031bn set in 2008 during the food crisis.

“With the pressure on world prices of most commodities not abating, the international community must remain vigilant against further supply shocks in 2011,” the FAO added. In the 10 years before the 2007-08 food crisis, the global bill for food imports averaged less than $500bn a year.

Hafez Ghanem, FAO assistant director-general, dismissed claims that speculators were behind recent price gains, saying that supply shortages were causing the rise.

Agricultural commodities prices have surged following a series of crop failures caused by bad weather.

The situation was aggravated when top producers such as Russia and Ukraine imposed export restrictions, prompting importers in the Middle East and North Africa to hoard supplies. The weakness of the US dollar, in which most food commodities are denominated, has also contributed to higher prices.

The FAO’s food index, a basket tracking the wholesale cost of wheat, corn, rice, oilseeds, dairy products, sugar and meats, jumped last month to levels last seen at the peak of the 2007-08 crisis. The index rose in October to 197.1 points – up nearly 5 per cent from September.

The FAO’s food index, a basket tracking the wholesale cost of wheat, corn, rice, oilseeds, dairy products, sugar and meats, jumped last month to levels last seen at the peak of the 2007-08 crisis. The index rose in October to 197.1 points – up nearly 5 per cent from September.

Agricultural commodities prices have fallen over the past week amid a sell-off in global markets, but analysts and traders continue to expect higher prices in 2011.

Friday, September 10, 2010

Global Food Supplies Tight

Agri-Food Price Index makes new high!

One road to wealth is to only own those assets for which the price is rising. That seems to be a rule that equity investors have forgotten. In any event, a great market technician once suggested only looking at those things with prices making new 52-week highs. His reasoning was that for the price of something to rise it must eventually make a new high. Well, based on the above chart, that technician would be all over Agri-Food commodities and associated investments. Our Agri-Food Price Index recently made a new high!

Recent embargo of grain exports by Russia due to problems with their wheat crops has served to highlight the tenuous nature of the world’s Agri-Food situation. Cessation of Russian exports did not cause prices to rise. It just helped to uncap them. The fundamental Agri-Food shortage facing the world did not suddenly arise. It has been building for years.

List of countries that cannot feed their people is not a short one. Included in it are all the nations of the Middle East, Egypt, India, China, Philippines, etc. With prosperity beginning to arise in China and on its way in India, these two nations will increasingly turn to global markets to feed their citizens. They have no choice, as they lack the land and all-important water to feed their people. In the global game of Agri-Food, those nations that bid the highest will get the food.

If one reads the commentaries or listens to traders, the discussion still drones on about absolute size of grain reserves in the world. And yes, they are sizable. That view, however, focuses on a meaningless metric. Gasoline stocks today are many times the size that existed when this author was a teenage driver. We are not, however, paying 19 cents a gallon for gasoline. For what matters is not the size of the reserves, but those reserves relative to consumption.

In our first chart this week, above, is plotted the days of consumption held in global reserves for the Big Four, corn, soybeans, wheat, and rice. They all fall into a range of 60-95 days. If no production of these grains occurred, in less than 60 days no corn would be available. In the case of rice, in less than 80 days none would be found.

Numbers in that chart do not portray a picture of overwhelming bounty. Such is the reason that global grain markets responded to the Russian announcement. At the same time, the world has really not yet come to know the impact of the floods on Pakistani rice production. That country is the number three exporter of rice.

New 90-week high about to happen?

When Agri-Food is short in supply anywhere, the world turns to North America. Per the latest USDA report, U.S. wheat export sales are running 60+% ahead of a year ago. For rice, the same number rounds to being up 30%. Those sales are tightening the prices of all grains, such as corn in the above chart.

Corn has not yet risen to a new 90-week high, but it is well on its way to doing so. China, long a net importer of soybeans, is now moving to becoming a net importer of corn. That importation takes two forms, physical corn and dry distillers grain. Latter is a byproduct of ethanol production. Essence of the problem for China is that it lacks the water to grow sufficient corn. Importing corn is the importation of “virtual water.”

When corn is $11 a bushel, who will benefit from it? Will your wealth? Two good ways exist to participate in the tightening of the global Agri-Food markets. One is through stocks of those companies that serve the global Agri-Food market. Second is through investment in Agri-Land. For those that might think in terms of the latter, our 4th Annual U.S. Agricultural Land As An Investment Portfolio Consideration - 2010 will soon be available at our web site. This report is the definitive annual study of the returns earned on U.S. agricultural land.

Friday, September 3, 2010

Overnight Commodity Recap

- * Raw sugar hits 6-month highs; coffee near 13-year peak

- * Wheat rallies a second day as Russian export ban stays

- * Copper closes off 4-month highs; oil off peaks too

- * Coming Up: U.S. jobs data for August on Friday

Monday, August 30, 2010

Pay Attention to Potash; It Will Affect You!

Note in this video how they try to avoid saying that food shortages are coming, but they speak about supply "pressure". There is a very good chance that food shortages are in the not-too-distant future! There! I said it because they won't!

Hugh Hendry is credible because his hedge fund is the top performing hedge fund thus far in 2010.

Friday, August 13, 2010

Healthcare Reform a Paperwork Nightmare for Farmers

U.S. Representative Adrian Smith, R-Neb., believes farmers face an administrative nightmare with President Obama's new health care law. Section 9006 of the law requires that all businesses file a 1099 with the Internal Revenue Service for every contractor from which they purchase $600 or more in goods or services in a calendar year.

During the weekly House Agriculture Committee Republicans feature the Ag Minute, Smith further explained the situation by saying that when a farmer or rancher spends $600 on feed corn, seeds, fertilizer, fuel, tractors or nearly every other expense, they will have to research and prepare a 1099 form for each and every purchase. He said this will prove to be an administrative nightmare for the nation's family farms.

In response, Smith has cosponsored HR 5141, the Small Business Paperwork Mandate Elimination Act, which will repeal this new requirement. According to Smith the nation's farmers and ranchers already have enough headaches when it comes tax time and Congress shouldn't be making them worse to pay for a misguided health care bill.

Thursday, July 15, 2010

Wednesday, July 14, 2010

Finance Reform Bill Will Send Terrible Ripples Through Ag Community

This is what happens when politicians run amok!

Far from Wall Street, President Barack Obama's financial regulatory overhaul, which may pass Congress as early as Thursday, will leave tracks across the wide-open landscape of American industry.

Designed to fix problems that helped cause the financial crisis, the bill will touch storefront check cashiers, city governments, small manufacturers, home buyers and credit bureaus, attesting to the sweeping nature of the legislation, the broadest revamp of finance rules since the 1930s.

Here in Nebraska farm country, those in the business of bringing beef from hoof to mouth are anxious, specifically about the bill's provisions that tighten rules governing derivatives. Some worry the coming curbs will make it riskier and pricier to do business. Others hope the changes bring competition that will redound to their benefit.

"Out here we like to cuss the large banking institutions because of the mortgage mess, but we also know that without them some of these markets don't work," says Mike Hoelscher, energy program manager for AgWest Commodities LLC, a Holdrege, Neb., brokerage that provides derivatives services to the farming industry.

Derivatives are financial instruments whose value "derives" from something else, such as interest rates or heating-oil prices. The first derivatives were crop futures, which appeared in the U.S. at the end of the Civil War and became a standard facet of business for companies across America.

During the financial crisis, they became notorious as American International Group Inc. and others were gutted by bad bets on derivatives linked to bad mortgages.

President Obama and other proponents say the financial overhaul will prevent the kind of reckless lending and borrowing that sank the financial system and left taxpayers with the check. They say non-financial companies are worrying unduly about the derivatives portion of the legislation. The Senate is expected to approve the financial regulatory overhaul on Thursday, sending it to the president.

The full impact won't be known for years, but in Nebraska nerves are already on edge.

Executives at Five Points Bank in Hastings think the new rules on mortgage lending will make the home-loan business less profitable. "When they create a new regulator, it really scares us," says Nate Gengenbach, vice president of commercial and agricultural lending.

Advance America Cash Advance Centers Inc. thinks the new Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection will take aim at the payday-loan business, though it's not clear what steps the agency will take. Advance America's storefront at the Skagway Mall in Grand Island charges an effective 460.08% annualized interest rate on a two-week $425 loan.

But it's the derivatives portion—the part of the bill aimed directly at Wall Street—that might end up touching most lives in rural America.

The new law requires most derivatives transactions be standardized, traded on exchanges, just like corporate stocks, and funneled through clearinghouses to protect against default.

Faced with intense lobbying, Congress partially exempted businesses that use derivatives for commercial purposes. So, farmers and co-ops probably won't face new collateral requirements, for instance—although there remains a dispute over that section of the bill. Those that trade derivatives on regulated exchanges, such as the Chicago Board of Trade, are less likely to see immediate impacts than those conducting private over-the-counter deals, which will face federal regulation for the first time. The goal is to make such deals transparent.

The question for these farmers is whether such rules will make hedging more expensive. Some say new requirements on big players will create higher costs for small players, including the cash dealers will have to put aside to enter into private derivatives transactions. Some brokers think restrictions on big-money banks and investors will drain the amount of money available to the everyday deals farmers favor.

Others predict the opposite effect, pushing money from the private market to the exchanges and creating more competition that will benefit farmers.

Uncertainty reigns in Giltner, a town of 400 residents 80 miles west of Lincoln. At first glimpse, Giltner's landscape seems featureless, a fading horizon of corn and soybeans. But its details are more subtle, including wildflowers and shaded creeks. Everywhere galvanized-steel sprinkler systems crawl across farm fields like giant stick insects.

Mr. Kreutz, an outgoing 36-year-old with a sandy crewcut and sunburned neck, gave up a career in finance and took over the 2,800-acre family farm after his father's death. As he works his fields, he checks the crop futures prices on his smart phone.

Here's how Mr. Kreutz does it: Say in early summer he sees that the price for a Chicago Board of Trade futures contract on corn for delivery later in the year is $3.56 a bushel. If he likes the price, and wants to lock it in, he calls AgWest and sells a futures contract for 5,000 bushels. The futures contract is a derivative in which the price for corn is set now for exchange in the future, though no kernels will change hands. Instead, when the contract nears expiration, Mr. Kreutz and the buyer of his contract will settle—in effect—by check.

By fall, when Mr. Kreutz is ready to deliver his crop to the local co-op, the market price might have fallen by 50 cents. He'll sell his actual corn for that lower amount. But he'll make up the difference through his financial hedge. (Mr. Kreutz buys a new futures contract at the lower price to make good on his earlier promise, making up the 50 cents.) In all, he'll have hit the price target he locked in earlier in the year, minus brokerage fees.

If the price rises during the summer, as it did during the food crisis two years ago, Mr. Kreutz has to pony up extra cash for his broker—a margin call—to maintain his positions. He recoups that by selling his actual corn at a higher price, but has to take a loss to meet the futures contract he signed earlier in the year, missing out on a windfall but ultimately meeting his target price.

Mr. Kreutz does this type of operation dozens of times a year, hedging about 70% of his 345,000-bushel corn harvest.

Such deals ripple through the local economy. When Mr. Kreutz gets a margin call from his broker, he turns to his banker, Mr. Gengenbach, for a loan to cover it. Mr. Gengenbach estimates that one quarter of his farm clients use derivatives.

"Somebody like Jim has a lot of money in his crop out here," says the 37-year-old Mr. Gengenbach. "If he can't protect that, it's not good for us."

Mr. Kreutz's brokerage, AgWest, thinks the new finance law will hurt both firm and farm. If big investors and dealers have to keep more cash on hand, there will be less liquidity in the market and therefore the cost of derivatives will increase, Mr. Hoelscher, the broker said.

A few minutes from the Kreutz family farm are the corrals of Jon Reeson's feedlot. Mr. Reeson, 43, is married to Mr. Kreutz's sister Jane. His feedlot holds as many as 1,500 steer, mostly Black Angus, which grow from 600-lb. calves into 1,300 pounders ready for slaughter.

Mr. Reeson uses derivatives to hedge both the price he pays for feed and the price he gets for selling his steer.

The fattening takes about 7,000 pounds of food for each animal. Mr. Reeson can't count on a favorable price from his brother-in-law's farm, in which he has a stake, so when he sees a feed price he likes, he seals it with a futures contract.

In April, he called AgWest and locked in a price with a futures contract for $95 per hundredweight of cattle. Since then the market price has dropped to $90. If the price stays there until October, he'll have made the right call, earning a higher price than if he'd relied on the market alone. If the price spikes higher, though, he'll miss out on potential gains.

Mr. Reeson is willing to live with that possibility in exchange for locking in a profit or a narrowed loss. Derivatives hedging helped him survive the recession of 2008-2009, when cash-strapped diners avoided steak and the price of beef plunged.

He's watching the new legislation warily and can't yet tell if it will hurt or help.

When his cattle have reached full weight, Mr. Reeson puts them on Roger and Barb Wilson's trucks for the trip to the slaughterhouse. The Wilsons have seven semi tractors and 16 trailers, and one of their biggest costs is diesel fuel to keep the fleet on the road.

In 2004, Cooperative Producers Inc., his local co-op, offered Mr. Wilson a price-protection plan for 10,000 gallons of diesel at about $2.50 a gallon, with 90 days to use it.

CPI had a choice. It could take its chances and hope the price of fuel would drop before Mr. Wilson took delivery on his full order, a windfall for the co-op. If diesel prices jumped, though, the coop would take a bath. "That falls under speculation," says Gary Brandt, CPI's vice president of energy. "But that's not what cooperatives do. That's what Goldman Sachs does."

Instead, CPI hedged on the New York Mercantile Exchange, buying a futures contract on heating oil, a close market substitute for diesel fuel. The co-op goes a step further and hedges also the difference between the prices of fuel traded in New York and delivered in Nebraska.

For the 57-year-old Mr. Wilson, the pricing plan proved a mixed blessing. The first year, the pump price shot up by another 20 to 25 cents, meaning he was getting a good deal. The following year the pump price dropped about a quarter a gallon, but Mr. Wilson was obliged to pay the higher price. "It hurt to have to pay for that fuel," he recalls sourly. He quit the program after that.

The finance law's imminence has prompted CPI's Mr. Brandt to warn his sales team and customers that the co-op may have to end its maximum-price fuel contracts. He's worried too that CPI might have to cut its fuel supplies if it can't hedge against price drops.

"We have to start making a game plan if they take away the ability for us to hedge that inventory," Mr. Brandt says.

The Wilsons deliver Mr. Reeson's steer to a low, cement-gray complex on the edge of Grand Island, Neb., where trucks arrive loaded with cattle, and others leave loaded with meat. Over the past year, Mr. Reeson has sold 1,125 steer to the packing plant, which is owned by JBS USA, a Greeley, Colo., unit of Brazilian-owned JBS SA.

JBS buys livestock two ways. Sometimes it pays cash for the following week's kill. Sometimes it buys further forward, agreeing in July, for instance, to a fixed price for steer delivered in December. JBS hedges on the derivatives market to make sure live cattle prices don't drop before it takes delivery.

The company also sells beef cuts forward to restaurant chains, promising delivery at set prices months ahead of time. JBS expects to have enough meat to fulfill the agreements. But if it runs short, it doesn't want to risk having to pay higher prices to buy meat to supply those restaurants.

So, it uses the derivatives market to play it safe. To do so, the company has to find a way to hedge different cuts of beef: Tenderloins might represent 1.5% of the total value of a steer. Strip loins might make up 3%. In a sense, JBS protects itself by reconstructing the steer through a derivatives trade on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. "We try to put the carcass back together financially," says company spokesman Chandler Keys.

The company hedges electricity for its refrigerators and natural gas for its boilers. It hedges currencies to stabilize its income from overseas. It hedges fuel for its fleet of thousands of trucks.

Even executives at a big firm such as JBS haven't been able to nail down the precise impact of the legislation on their business, introducing an unaccustomed level of uncertainty into their operations. They aren't changing the way they use derivatives, yet, hoping instead that exemptions for commercial users will insulate them.

"To get food, particularly highly perishable food like meat and poultry, through to the consumer, you have to manage your risk," says Mr. Keys.

Monday, April 26, 2010

Americans Ignorant of Blessings of Modern Ag Techniques

It was truly a butt kicking. An old fashioned whipping. We lost the debate, and it wasn't even close.

I had been invited to New York City to debate the statement, "Organic food is marketing hype." We had 20% of the Manhattan audience on our side when the debate started and the same number on our side at the end. The undecided audience members at the beginning of the evening broke almost unanimously for the opposition. You can see the whole thing at In the window at the end of this blog.

The debate winner is the side that changes the most minds, and we were beaten like a rug. It will take a long time and much thought for me to come to final conclusions about the experience, but here are some first impressions.

Ferocious attacks I was totally unprepared for the ferocious attacks on conventional farming. One of our opponents said that one in eight children have birth defects, and strongly implied that my farm chemicals are the cause. The food critic for Vogue Magazine, who is a regular on the Food Channel, informed us that the days of the conventional farmer are numbered.

I was unprepared for the concentration on animal welfare. Sure, I expected they'd accuse farmers of being careless about the land we farm, but I never thought that I would be accused of "raping" the soil with the fertilizers I apply. 'Great Lakes-sized lagoons full of Poo?' What's this poo business? You can't say manure? Animal waste?

Actually, poo was much on the mind of the most effective debater on the other side. Poo fed to cows, poo falling on chickens' heads in cages, human poo prohibited as fertilizer for organic farmers, but used by conventional farmers.

Most of the poo in this debate was thrown against the wall by the other side, and a good deal of it stuck. They were more skilled, and more shameless. There are no fact-checkers in a debate, no editors, and no chance for a do-over. I've thought of a reply to most every claim…72 hours too late.

People in the audience laughed when I said that the application of science to farming had been a good thing; that it has been a boon for the human race that yields are increasing; that genetically modified seed and fertilizer and pesticides have helped feed the world; that we were richer because of modern agriculture.

They laughed when my team member pointed out that modern pig farming has actually lessened the chance of swine-to-human movement of flu viruses. The knowledge about actual food production in that auditorium was nonexistent. If we are to continue to engage our critics, we're going to have to start at the beginning. People really don't have a clue about on-the-ground facts of farming.

Better story-telling I'm not sure how we tell our story better. I'm not sure how we win this argument. It didn't seem adequate to point out that there are environmental costs to organic farming. (Our Vogue food critic informed us that organic farmers didn't till the soil, and that knee high weeds in the field didn't hurt yields.)

This audience, at least, wasn't particularly interested in the fact that people would be hungry if organic farming is so widely practiced that a quarter of U.S. crop ground is in legumes to provide nitrogen for the next years' corn or wheat crop. The fact that plants produce natural pesticides, and that many of those natural pesticides are carcinogenic, didn't change a single mind.

An audience member asked if there was a scientific test to determine whether a crop had been raised organically. Our opponents dodged the question, but it was clear that testing wouldn't show many discernible differences in quality. When one of our team members said there was a test that would show whether commercial fertilizers had been applied to a crop, the other side wasn't the least bit interested.

A cynic might say they were afraid that testing organic crops might prove that some food marketed as organic...isn't. It did seem odd to me that every restaurant, food stand, and small grocery in Manhattan advertised organic produce. If total organic production nationwide is only 3% of the supply, the market penetration in Manhattan is closer to 100%.

We have to learn what messages work, and what messages do not. I'd love to see a focus group study the debate, and find out if anything we said had an effect on the audience.

We conventional farmers have to get better at this, or we're headed toward some major changes in the way we farm. I don't want to face that future, and I don't think it's good for our nation, or the world. But we're losing this battle, and our debate was just one small indication of that terribly depressing fact.

ORGANIC FOOD IS MARKETING HYPE from Intelligence Squared US on Vimeo.