One of the interesting things about being in Hong Kong is that I get to see the weekend edition of the Financial Times 12 hours early. And the headlines were not all that pleasant. As I promised last week, we will cast our eyes to Europe and ponder what is in store for Europe for the year and the next five years. And what do we read on page 2? The "ECB raps revisions to draft a fiscal pact." Seems they feel there are too many loopholes, which will make the document meaningless … somewhat like the treaty they have now. And we further learn that "Greek default threat grows as talks falter." Seems there is a lack of agreement on how much of a haircut the investors ought to take, and the Greeks don't want to guarantee any future debt, just in case they need to default some more in the future. But they do want the €15 billion they need to keep the debt machine running for a few more months.

And on page 1, in big type, we are surprised (but not very) by the headline, "France and Austria face debt blow." Seems those sharp-eyed accountants over at S&P have decided to downgrade French debt from AAA. Which of course leads to another headline on page 2, suggesting "Firepower of bail-out fund cast into doubt." The currency markets were shocked – shocked I tell you – that S&P would do such a thing and promptly took back the euro rally and cast the euro down to recent cycle lows. Who knew, other than the entire free world not watching reality TV, that S&P was planning to do such a thing? And we read elsewhere that the European Commission is dismayed that S&P would do something so clearly not right, at least according to the way they keep their own books.

Even here in amazing Hong Kong, with the growth of China driving a wave of prosperity, eyes are fixed on Europe. How will they deal with the crisis? We read that US exports to Europe were down 7% last quarter, and Europe has not yet really entered into recession, which is almost guaranteed this year. And if US exports are down, then so are Asian and Latin American exports. Global growth appears to be threatened.

There are so many pieces of data to go through in order to augur Europe's future – I want readers to know I have left no stone unturned! In fact, I went to some very old stones to get help with this week's letter. I began to scrutinize the Mayan Code from ancient Central America, which so many feel predicts the end of the world on December 21 of this year, bringing my fresh eyes to an old mystery.

After much deliberation, I have come to this astounding insight: The Mayan academics who created the code were not in fact astronomers or even astrologers. No, it is clear they were another breed of even more dubious forecasters, called economists. Once you approach the glyphs with that understanding, it becomes clear they are not predicting the end of the world, merely the end of Europe. One symbol clearly shows the Greek flag dipping to the ground. Another depicts the Italian flag with its wheels coming off. Oh, and you don't even want to know what they have prognosticated for the French. This is a family e-letter and I can't squeeze such language past the censors. But now that I have provided the basic insight, I leave it to you, fellow scholars, to decipher the rest of code.

And we will spend our time together here this week trying to discern what it means, in fact, for Europe to come to the place in its journey where it must make extremely difficult and often painful choices. As I wrote last week, as I started this voyage of discovery with you, the choices the various countries in the developed world are now making will put us on a path that does not allow us to turn back without severe consequences. (If you missed last week's letter,

here it is.) We are left with debt that must be dealt with, with imbalances that must be balanced, and with deficits that must be brought under control. No matter what we choose, there will be pain for all of us. You cannot make debt go away without paying it back or defaulting, one way or the other, which means someone loses. And as we will see, paying it back can be very difficult, indeed, once it has grown this large.

There are three main problems in Europe. The first is that most of the banks are massively insolvent, because they have 30 times their capital invested in the second problem, which is the sovereign debt of countries that are going to have trouble paying that debt. If the banks have to mark down the debt to what its real value is – or to what it will soon be – they will be bankrupt on a scale that makes 2008 look like a waltz in the park.

Countries simply cannot function in a manner that can be called normal without viable banking systems, which is why the authorities spend so much time worrying about them. If banks can't make loans, then businesses must cut back, which means fewer jobs, products, and services, which quickly becomes an ugly spiral. Losses in the private sector mount up. This obliges the treasury secretary to get on one knee and beg some elected official who has no understanding of how business and economics work to save the world as he knows it.

But if countries must step in and save their banks, then they have to assume some of the losses. (I am assuming that this time shareholders get completely wiped out, as do most bondholders. Taxpayers – read voters –are actually paying attention this time. They are in no mood to bail out bankers.) But most of the countries in Europe with the worst banks simply do not have the money to invest. They already have too much debt. Where do they get the capital? (More on that later.)

For most of the past two years, European leaders have tried to deal with the problems as though they were short-term liquidity problems: "If we just find the money to buy some more Greek bonds, then Greece can figure out how to solve its problems and then pay us back. Given enough time, the problem can get solved."

They have now arrived at the understanding that it this not a short-term problem. Rather, it's a solvency problem of the various governments, which of course creates a solvency problem for their banks. They are now addressing the problem of solvency and providing capital until such time as certain countries can get their budgets under control and the bond market sees fit to provide the capital they need.

But they are completely ignoring the third and largest problem, and that is massive trade imbalances. Germany exports products to the peripheral European countries, which run trade deficits. As I have shown in several letters, a country cannot reduce private-sector leverage, reduce public-sector leverage and deficits (balance its budget), and run a trade deficit all at the same time. That is simple, unavoidable math, based on 400 years of accounting understanding. Ultimately, there must be a trade surplus if leverage and debt are to be reduced.

Greece runs a trade deficit of about 10% of GDP. Until they can stop that bleeding, they cannot get their government and private budgets under control. It is not simply a matter of cutting budgets or raising taxes. Indeed, their economy will continue to shrink, making it more difficult buy foreign goods without increasing their own production of goods and services. It is a vicious spiral. And that same spiral will spin up to take in all of Europe. Again, more on that later, as we consider what their choices are.

But for now, let's start with my contention that if you do not solve all three problems you do not solve the real problem. Greece cannot "stand on its own" without a change in its cost of production relative to Northern Europe. Neither can Portugal, et al., unless Germany either changes how it exports and consumes more, or Germany is willing to fund Greek (and Portuguese and Italian and…) debt, so those countries can continue to run large deficits.

Let's resort to something I have done in the past, and that is to create a simple model to help us understand the issues involved. As always, when we make simple assumptions we are ignoring the real complexities. I know things are vastly more complicated than the following simple analogies, but the underlying truths are basically the same.

Let's assume a country that has a gross domestic product (GDP) of $1,000. In the beginning it taxes its citizens about 25% of GDP and spends the money for the public's benefit. But alas, it spends about 30% of GDP, so it must borrow the overage (about $50) from its citizens or from the citizens of other countries. Because the country starts out with relatively little debt, interest rates on this loan are low, because those who buy the debt can easily see that the the country can pay them back. If the debt of the country is only 5% of GDP ($50) and the interest rate is 4%, then the amount that must be paid as interest is only about $2 per year. Not a whole lot, about 0.2% of GDP.

But this goes on year after year. Sometimes the deficits get smaller and sometimes they get larger, depending on the economy; but government expenditures grow at the same rate as the country grows, and the debt keeps growing at an average of 5% of GDP per year. Now, if the country is growing at 3% a year, after 24 years the economy will have doubled to $2,000 GDP. That means the debt has grown (roughly) to a total of $1,800, which is now a debt-to-GDP ratio of 90%. Debt has grown faster than the country's economy. Note that if the country had held its budget down to where it grew slower than GDP, thus reducing its need for debt, that ratio would be lower, even if the debt had grown. You can indeed grow your way out of a debt problem if the growth of government spending is less than the growth of the economy.

But what if the size of government grows to about 50% of GDP, rather than 25% or 30%, over the 24 years, as politicians decide to spend more money and voters decide they want more benefits? (Think France.) Then the private sector must pay about 50% of its production to the state – plus, the debt is now growing unwieldly. The private sector has less to invest in new businesses and tools, and the growth of the economy slows.

And then along comes a very nasty recession. The revenues of the government fall as the economy shrinks. If the economy shrinks by 3% and total taxes are 50%, then tax revenue falls to $970. But the government does not cut back; and indeed, because it must pay unemployment benefits and welfare (because unemployment rises in a recession), its expenses actually rise by 5%! So it now needs $1,050 to pay all its budgeted expenses. And it must now borrow $80 to pay everyone it has promised to pay, in addition to the $100 it was already borrowing every year to cover its deficit, or a total of $180 a year, which is 9% of GDP.

(Yes, I know that debt must change as a percentage over time and nothing is stagnant, but work with me here.)

Now debt-to-GDP is rising by about 5% a year. Not a large number in the grand scheme of things, and everyone knows that the recession will soon be over and the deficits will come down. Sovereign governments never default on their debts – our government leaders assure us of that. They can always raise taxes or cut spending, can't they?

And things rock along just fine, and the bond market continues to buy the debt, until one day you look up and the debt is 120% of GDP. Then the bond market gets nervous and says that instead of 4% it wants 7%. Now the interest payments are over 8% of GDP and 16% of government spending, which means the government must either cut back on services or salaries or benefits, or raise taxes, or borrow more money. But cutting spending and raising taxes have consequences. They reduce GDP growth over the following 4-5 quarters as the economy adjusts.

What if that interest rate cost rose to 10%? Then the interest cost to the government would become 20% of its expenses and be rising faster than the country could grow, even in the best of times. And if they continued to borrow at 7% and the country did not grow, those interest expenses would rise at least 7% a year – as long as interest rates didn't go up.

And what if the other countries who had been buying the government's debt looked at the basic math and realized that, another step or two down the current path of government spending, there was no way they would be able to get their money back?

Now, government bond investors are a curious breed. They invest in government bonds because they actually think there is not supposed to be any risk. They want their money to be safe. If they wanted risk, there are lots of opportunities to invest with the potential for more reward.

The moment that government bond investors begin to think they might be at risk, they leave. And history suggests they tend to leave seemingly all at once. It is the Bang! moment. Someone fires the starting gun, and they all head for the exits. They start selling their bonds to speculators at discounts, which makes the effective interest rates in the market rise, sometimes by a lot. That means that if a country wants to borrow more money, it will have to pay the effective price in the market, or maybe as much as 15-20% IF – a big IF – it can even get someone to buy the bonds, which of course makes it even more difficult to pay their debt as interest costs rise.

Now, let's add a twist. The other countries that have bought those bonds are not actually countries, but banks in other countries. And because the regulators of those banks knew it was impossible – inconceivable – that a sovereign country might default, they allowed their banks to buy 30 times as much sovereign debt as they had capital in their banks. They did not have to reserve against any losses, so these were "free" profits for the banks. You pay 2% on deposits or short term commercial paper and buy bonds paying at 4%. You make a 2% spread, which you then do 30 times. Now you are making 60% profits on your capital and deposits. It is a

very nice business – as long as everyone pays the interest. And because it is such a good business, you just roll over the debt every time the bond comes due, because you want more easy profits.

Let's say that banks bought up to 10% of their total government sovereign-debt holdings in our problem country. If the country gets into trouble and says, we will only pay 50% of our debt (we will discuss why below), then that means the banks lose 5% of their total assets. But they only have about 3% capital, because they were allowed to leverage. That means they are functionally bankrupt.

Without a functioning banking system, other countries now have to step in and take the losses (and perhaps wipe out the shareholders and owners of their banks). That would be bad for the other countries, as that much spare cash is not just lying around in government coffers. They are ALL borrowing money already and have their own deficits to worry about.

So everyone gets together and they tell the bankrupt country (because that is what it really is), we will lend you more money to keep you alive, but you must agree to balance your budget. And since that is the only way the problem country can get more money, they initially say, "Sure. We can do that. Just give us some money now so we can get it figured out and get everything under control."

In the world of government, living within your means is called austerity. And it's an uphill slog. Let's say your deficit started out at 15% of GDP (somewhat like Greece's). If you agree to cut that deficit by 4% a year for four years running, if everything stays the same, you could be back in balance. But the other counties would have to agree to lend you the difference between what you budgeted to spend and what you took in as tax revenues. Just to keep things going. Otherwise you'd have to default on your debt. If the countries simply have to guarantee the loans and not actually spend the money, it is a lot easier than having to find real money to save their banks, so they agree.

But the cuts you have to make are not as easy as everyone hoped. It seems that employees don't like having their pay cut, and unions don't want pensions cut, and retirees certainly expect the government to fulfill its promises; and don't even get started on cutting healthcare, which is a God-given right.

So you raise taxes and cut spending by about 4% the first year. But a funny thing happens. That reduces the private economy by about 4%, so the base on which taxes are collected is reduced, which means less revenue is raised, which means that the deficit is much worse than projected. And then the following year you have to make another 4% in cuts, plus the last shortfall, just to make your plan and get to the agreed-upon deficit, in order to get more loan money. It becomes a very vicious circle.

And let's look at the endgame. That debt-to-GDP ratio will rise to at least 150%, while the economy is actually shrinking. If interest rates settle to a mere 7% (hardly likely), it means the people of the country are going to have to pay over 10% of their total production to foreign banks each and every year for decades, never mind paying down the principle.

Let's throw in one more twist. The country has been buying about 10% of GDP more from other countries than it sells to them. That is because the relative wages in the problem country are about 30% higher than in the "good" countries. The good countries get the money from what they sell and have a nice surplus. The problem country soon runs through its savings, trying to buy the goods and service it wants; and the private sector, as well as the government, must cut back.

What happens is that you are locking in what feels like a depression initially, and then you have a slow- or no-growth economy for many years, as so much of your work goes just to pay back that debt to the banks of other countries.

Understand, your government has freely obligated itself to pay that debt. But it means that its citizens in effect become debt slaves for a generation or two to foreign banks. Not a very popular platform for a politician to run on for re-election.

Long-time readers know I think the neo-Keynesians do not have a proper view of the world. They live in a theoretical world divorced from what really happens. But in this respect they are deadly right. Austerity on the scale needed by many countries will only reduce potential GDP. The Keynesian prescription is to therefore run deficits and borrow money until you get growth again; but when you have already exhausted your ability to borrow money, it just doesn't work.

More debt makes if far more difficult to grow your way out of the problem. If you are already drunk, you can't get sober by drinking more whiskey. If Greece cuts its deficit by 15% of GDP, the reality is that GDP over time will be reduced by about 20%, and the debt will grow, both in real terms and as a percentage of GDP. A 20% decline in GDP is by any standard a depression and makes it even harder to grow, as so much of what you do make has to go to basic expenses and not productive capital. And if you have the burden of massive debt it becomes damn near impossible.

That is why individuals can file for personal bankruptcy. We no longer force people into slavery or debtor's prison to pay their debts, at least in most places.

So our problem country goes to its lenders and says, "We think you should share our pain. We are only going to pay you back 50% of what we owe you, and you must let us pay a 4% interest rate and pay you over a longer period. We think we can do that. Oh, and give us some more money in the meantime. And if you refuse, we won't pay you anything and you will all have a banking crisis. Thanks for everything."

The difficult is that if our problem country A gets to cut its debt by 50%, what about problem countries B, C, and D? Do they get the same deal? Why would voters in one country expect any less, if you agree to such terms for the first country?

So now let's return to the real world of Europe. Greece cannot pay its debt without a major depression. So its wants to pay only 50%, but it doesn't even want to guarantee that in any meaningful way; so bondholders scream, "We get nothing in return for agreeing to take a 50% haircut?!" Which is today's headline.

Greece cannot print its own money, so unless it leaves the Eurozone, it's stuck. They can default on their debt, but that means they are shut out of the bond market for some period of time. That would force them to make the spending cuts they are now resisting, as they would simply not have enough money to pay their bills. Even with a 100% haircut they're looking at a shorter but very real depression. And because no one will sell them products they need, like energy and food and medicine, unless they can sell or trade something in return (that trade-deficit problem), they will be forced to change their lifestyles. Wages must drop or productivity rise to be competitive with northern Europe. And that differential is about 30%. I am not certain, as I have not been to Greece in a long time, but my bet is, you won't find many Greeks who think they are overpaid by 30%.

But that is what the market is going to say. And that is the third problem, which Europe is not addressing. Germany and the northern tier are simply more productive than the Southern periphery. (With the possible exception of Northern Italy, but Italy all gets lumped together, which is why many Northern Italians want to be their own country and not have to pay taxes that go to Southern Italy. I am not taking sides, just observing what we read in the papers.) Until Germany consumes more from the peripheral countries or the peripheral countries become more productive, the imbalance will not allow a positive solution.

Prior to the euro, the imbalances would be handled by currency exchange rates. The value of the drachma would go down relative to the value of the deutschmark. Things would balance over time. Now, all of the eurozone countries are effectively on a gold standard, with the euro standing in for gold this time. Britain, the US, and Japan print their own currencies. Their currencies can rise or fall over long periods of time, based on national accounts and the desires of foreigners to buy goods or invest in their countries.

Greece and the other peripheral countries face a difficult choice. Do we stay in the euro and pay as much as we can, and watch our economy drop; pay nothing and watch our economy drop (as we get shut out of the bond market); or leave the euro and go back to our own currency and watch our economy drop?

They have no choices that allow them to grow and prosper without first suffering (for perhaps a long time) some very real economic pain. As I have written in previous letters, leaving the eurozone has severe consequences; but the economic pain of leaving would go away sooner and allow for quicker adjustments, than if they stayed. However, the initial pain would be worse than the slow pain they'd suffer by staying in the euro. Their choice is, simply, which pain do they want – or maybe, which pain do they think they want? Because whatever they choose, they are not going to like it.

And just as I was finishing this section, this note came from Naked Capitalism:

"The three Troika inspectors—Poul Thomsen from the IMF, Mathias Morse from the EU, and Klaus Mazouch from the ECB—are supposed to head to Greece next week to inspect its books; the budget deficit is once again higher than the revised limit that Greece had vowed to abide by. And they're supposed to negotiate additional 'structural reforms.' But there probably won't be three inspectors,

according to senior IMF sources. Missing: Poul Thomsen. The IMF has had enough.

"Already, according to more

leaks, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde had warned German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Nicolas Sarkozy that the fiscal and economic situation in Greece had deteriorated. Hence, the 'voluntary' haircut on Greek bonds held by private sector investors should be increased to more than 50% to maintain the goal of bringing Greece's debt load down to 120% of GDP. And the second €130 billion bailout package, agreed upon on October 26, should be enlarged by 'tens of billions of euros.'

"The German reaction was immediate. 'There has to be a line somewhere,'

said Michael Fuchs, deputy leader of Merkel's party, the CDU. 'This cannot be a bottomless barrel.' Even if Merkel were amenable to committing more taxpayer money to bail out Greece, she'd face a wall of opposition in her own party. And he wasn't brimming with optimism: 'I don't think that Greece, in its current condition, can be saved,' he said."

The article goes on with a description of the chaos in Greece. It is worse than I have described. Really. And so terribly sad.

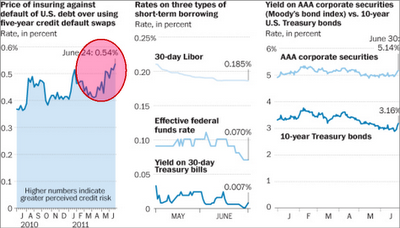

Before I hit the send button this week, let's look at a few charts that can help us judge the current scope of the problem. These are from the very astute Bill Hester of the Hussman Funds. He wrote a very solid piece entitled "Five Global Risks to Monitor," at

http://hussmanfunds.com/rsi/fiveglobalrisks2012.htm. It is very good, if sobering, reading.

This first chart shows how much bank debt is maturing in Europe over time. You have to add in how much new debt must be sold, as they will need to raise capital to balance the sovereign debt losses. Do you have a spare €1.5 trillion? Yes, some of that is rollover debt, but banks are trying to reduce their exposure to each other and may not want to roll over that debt, unless they can turn around and get capital from the European Central Bank to buy it, which is a back door to debt monetization.

The next chart shows how much debt must be rolled over by governments in the coming year. Notice how much Italy must raise in the first three months!

And one last chart from Hester. This is the rise in the cost of new debt as older, cheaper debt comes due. My simple example is not at all extreme.

Next week we will look further into Europe. As a preview, I do think this is the year they will be forced to the very hard decisions. We will examine what a fiscal union would look like and how likely it is to happen, and what the prospects are for a break-up of the eurozone, and compare several scenarios for what Europe may look like in five years.