Tuesday, December 28, 2010

Sunday, December 26, 2010

There's a Run on Bond Funds

from Bloomberg:

Bond mutual funds had the biggest client withdrawals in more than two years last week as a flight from fixed-income investments accelerated.

U.S. bond funds experienced withdrawals of $8.62 billion in the week ended Dec. 15, up from $1.66 billion the week before, according to a release from the Investment Company Institute, a Washington-based trade group. Last week's withdrawals were the largest since the week ended Oct. 15, 2008, when investors yanked $17.6 billion from bond funds.

Investors are retreating from bond funds after signs of an economic recovery and a stock market rally increased speculation that interest rates may rise. The selloff in Treasurys accelerated after the Federal Reserve last month pledged to buy $600 billion in assets to revive the economy. The 10-year note yields 3.35 percent, up from 2.49 percent Nov. 4, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Most of the money was probably pulled by institutional investors looking to lock in higher yields by buying bonds directly, rather than through funds, said Geoff Bobroff, a consultant based in East Greenwich, Rhode Island.

"I would guess most retail investors are staying put because you aren't seeing the money go anywhere else," he said in a telephone interview.

Vanguard, Pimco

Removals included $3.77 billion from taxable bond funds and $4.85 billion from municipal bond funds. U.S. stock funds had withdrawals of $2.4 billion while foreign equity funds attracted $2.24 billion in the week, ICI said.

Investors put $245 billion into bond mutual funds this year through November, bringing net deposits since the end of 2007 to $636 billion, according to data from Chicago-based Morningstar Inc. Vanguard Group Inc., based in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, had deposits of $33.4 billion into its bond funds through November while Franklin Resources Inc. of San Mateo, California got $23.7 billion, Morningstar data show.

Pacific Investment Management Co., the Newport Beach, California-based firm that runs the world's biggest mutual fund, attracted $57 billion to its bond funds in the first 11 months of the year.

The $250 billion Pimco Total Return Fund, managed by Bill Gross, had its first net withdrawals in two years in November as investors pulled $1.9 billion, Morningstar reported. Pimco Total Return this month said it is expanding its policy to allow investments in equity-linked securities for the first time since 2003.

"Fixed-income has been the lifeline for a lot of these firms," Douglas Sipkin, an analyst with Ticonderoga Securities in New York, said in an interview earlier this month.

Pimco this month raised its forecast for U.S. economic growth next year as policy makers pump a "massive amount" of stimulus into the economy, Chief Executive Officer Mohamed El-Erian said.

Sunday, November 7, 2010

Hussman: QE2 Just More Bubble and Crash Economics

"Stock prices rose and long-term interest rates fell when investors began to anticipate the most recent action. Easier financial conditions will promote economic growth. For example, lower mortgage rates will make housing more affordable and allow more homeowners to refinance. Lower corporate bond rates will encourage investment. And higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. Increased spending will lead to higher incomes and profits that, in a virtuous circle, will further support economic expansion."

Monday, October 11, 2010

QE2 Will Be Either A Small Or Massive Failure

In his latest letter Van Hoisington cuts through the bullshit and asks the number one question (rhetorically): why are bank excess reserves (aka the ugly, liability side of Quantitative Easing) still so high. He answers: "Either the banks: 1) are not in a position to put additional capital at risk because their balance sheets are shaky; 2) are continuing to experience large write-downs on commercial and residential mortgages, as well as on a wide variety of other loans; or 3) customers may not have the balance sheet capacity or the need to take on additional debt. They could also see no expansionary prospects, or fear an uncertain regulatory future. In other words, no viable outlets exist for banks to loan funds." Which leads him to conclude quite simply that while risk assets may hit all time highs courtesy of free liquidity, the economy, also known as the middle class, will be stuck exactly where it was before QE2... and QE1. Van also looks at that other critical variable: velocity of money - "Velocity is primarily determined by the following: 1) financial innovation; 2) leverage, provided that the debt is for worthwhile projects and the borrowing is not of the Ponzi finance variety; and 3) numerous volatile short-term considerations." As an uptick in velocity is critical for any wholesale reflation (as opposed to merely hyperinflation) plan to work, this is one metric Van is unhappy with. Lastly, Hoisington also looks at the fiscal headwinds facing the country (which more so than anything terrify the Goldman economics team), and presents his vision on the bond-bubble argument.

Still Vulnerable

Hoisington Investment Management

By Lacy Hunt and Van HoisingtonOctober 8, 2010

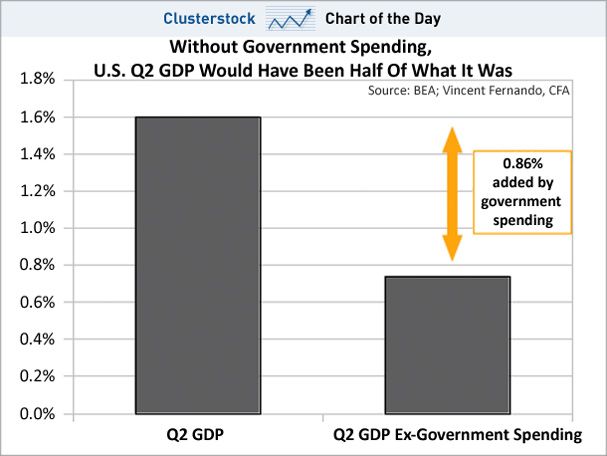

Despite extreme economic intervention by federal authorities, real GDP has increased by a paltry 3% since the recession ended in June 2009, less than half the 6.6% average growth in the comparable periods of the prior ten recoveries.

Inventory investment, a trendless component of GDP, has accounted for nearly two-thirds of the entire rebound in economic activity from the worst economic contraction since World War II. Over the past four quarters, inventory investment has moved from contracting real GDP at a 5% annual rate to boosting it at a 2% annual rate. Real final sales (GDP less inventory investment) grew at a very meager pace of 1.1%, less than one-fourth the average 4.5% rate of increase in the comparable rebounds. Whether measured by GDP or final sales, economic growth needs to expand at least at the pace of population growth to sustain a steady standard of living. In this rebound, per capita real final sales grew by 0.2%, much lower than the earlier ten postwar expansions when the growth in real per capita sales was a robust 3.2%. Thus, the U.S. standard of living has remained stagnant at a very depressed level. The upward inventory thrust is complete, and probably over-extended (Chart 1).

Another Failed Attempt--QE2

The flaccid nature of this business recovery should serve notice that economic conditions are far more precarious than generally understood. Federal Reserve forecasts were obviously flawed and have now been significantly lowered since they placed great emphasis on the presumed stimulative power of massive deficit spending and numerous aggressive monetary actions. The Fed is contemplating another round of quantitative easing (QE2) because the weakness of the economy has surprised them. They are feeling the political pressure to act, even though the problems facing the economy are not related to monetary policies.

The Fed’s position seems to be that more of the same economic policies are needed, even though they have failed to produce the advertised results. As microeconomist Steven Levitt (author of Freakonomics) documented, conventional wisdom is generally flawed since it fails to ask the right question about economic problems. We view the Fed's econometric model as the personification of conventional wisdom.

For instance, as a result of QE1 the banks are holding close to $1 trillion of excess reserves. The important question is why are banks unwilling to put these essentially zero earning reserves to work. Either the banks: 1) are not in a position to put additional capital at risk because their balance sheets are shaky; 2) are continuing to experience large write-downs on commercial and residential mortgages, as well as on a wide variety of other loans; or 3) customers may not have the balance sheet capacity or the need to take on additional debt. They could also see no expansionary prospects, or fear an uncertain regulatory future. In other words, no viable outlets exist for banks to loan funds.

A parallel situation exists in the corporate sector. Non-bank corporations are sitting on huge cash reserves. In the past two quarters liquid assets amounted to 7% of total assets, the highest level since 1963 (Chart 2). This cash reflects a lack of compelling uses for the funds, as well as the need to hedge against risks, including those of dealing with potential vulnerable counter-parties. The fact that substantial bank and corporate funds remain idle is a strong signal that U.S. economic problems exist outside the monetary sphere.

The problem with the U.S. economy is fourfold: 1) The economy is grossly overleveraged, with many asset prices falling; 2) fiscal policy is counter-productive and debilitating to economic growth as government expenditure multipliers are near zero; 3) proposed tax increases are already curtailing economic activity and tax multipliers approach -3%; and 4) increased bureaucracy with many new and yet unwritten regulations from the Dodd-Frank bill, along with health care regulations, make business planning nearly impossible.

With existing excess liquidity in banks and companies, and the above-mentioned key economic problems, it should be clear that QE2 and the purchases of additional assets by the Fed will, like previous purchases in QE1, serve only to bloat excess reserves without advancing income, spending, or jobs. From this point in the cycle, for QE2 to generate expansion, money growth and therefore debt levels would have to rise.

According to economist Hyman Minsky, there are three phases of credit extension: hedge finance, speculative finance, and Ponzi finance. In view of the extremely leveraged conditions, additional credit would be almost exclusively of the Ponzi finance variety – loans with no reasonable prospect of repayment. Indeed, Ponzi finance appears to typify the bulk of the loans being made by the Federal Housing Authority to unqualified home buyers, replicating the practices underwritten by FNMA and Freddie Mac during the heyday of the sub-prime lending extravaganza whose consequences linger. But, for the purpose of argument let’s assume that with additional excess reserves the banks lend to other potential Ponzi-like borrowers. This could lead to an increase in the money supply, but the net result may still not stimulate faster growth in GDP because velocity would fall, as it did from 1997 to 2007 (Chart 3).

The Velocity Impediment

For a rise in excess reserves to boost GDP, two conditions must be met. First, the money multiplier must become stable. Second, the velocity of money must not decline. The second condition is not likely in view of the theory and history of velocity. Velocity is primarily determined by the following: 1) financial innovation; 2) leverage, provided that the debt is for worthwhile projects and the borrowing is not of the Ponzi finance variety; and 3) numerous volatile short-term considerations.

Since 1900, M2 velocity has averaged 1.67, and has demonstrated distinct mean reverting tendencies (Chart 3). Velocity has been declining irregularly since Ponzi finance took over in the late 1990s. For leverage to lead to an expansion of velocity the loans must meet the requirement of hedge finance, i.e., where there is a reasonable expectation that the borrower can repay both principal and interest.

Fundamentally, the secular prospects for velocity have not improved even though velocity recovered by 2.1% in the past four quarters. This marginal uptick in velocity reflected an assist in federal spending along with the unparalleled recovery in inventory investment discussed previously. Without the gain in these two GDP components, velocity was unchanged over the past four quarters (Table 1).

The Fed's adoption of QE2 may lead to severe unintended consequences. There are two possibilities: 1) QE2 does manage to temporarily improve GDP via continued overleveraging of the economy with non-repayable loans, 2) QE2 goes into the history’s dustbin of failed projects, along with QE1, cash for clunkers, tax credits for first time home buyers, and other numerous failed attempts to boost the economy with rebate checks.

For QE2 to work, a renewed borrowing and lending cycle must take place, resulting in a further leveraging of the already highly overleveraged U.S. economy. Such additional leverage would not be beneficial since increasing indebtedness from these levels ultimately leads to economic deterioration, systemic risk, and in the normative case, deflation, as documented by Rinehart and Rogoff in their book, This Time Is Different. Therefore, at best QE2 can be nothing more than a short-term panacea exacerbating the serious structural problems already facing the United States.

A Branch of Congress

More important, however, is that by implementing QE2 the Fed could eventually lose its historical independence. The Fed is facing some economic headwinds over which they have no control, and thrusting itself into situations with enormous potential for unintended consequences. If the Fed takes additional actions that are as ineffectual as they have been previously, this could lead Congress to assume that the Fed should be given more direct instructions regarding the purchase of financial assets. Congress might assume that QE1 and QE2 were unsuccessful because they were too small, not that they are fundamentally flawed concepts. On such a path, monetary policy could then become a mere branch of fiscal policy--a road to economic perdition.

Fiscal Headwinds

As an example of the headwind the Fed faces, consider present fiscal policy. Between the taxes in the 2010 medical reform law and the sunsetting on the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, several credible researchers calculate that taxes will rise about $3 trillion over the ten-year period starting in January ($1 trillion of medical law tax increases and $2 trillion of increases resulting from the sunsetting of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts). The vast range of tax increases include rising marginal rates for all tax brackets: the return of a marriage penalty, a 50% reduction in child tax credit, lower dependent care, adoption tax credits, return of death tax to 55%, rising capital gains and dividend taxes, elimination of health savings accounts, special needs tax caps, return of alternative minimum tax impacting twenty eight million families, shifting of expensing by small businesses, elimination of charitable contributions from IRAs, and inclusion of employer-paid health insurance on individual W2s.

A tax multiplier in the mid range of estimates (-2) is a contractionary force of $6 trillion, or $600 billion per year on average for the next decade. For an economy that grew only $500 billion in the past four quarters (including the aforementioned inventory surge), this tax blow is too large for such a fragile economy to absorb, and beyond the scope of any monetary policy. In addition, a new array of bureaucrats necessitated by new regulations have increased uncertainties and problems, making planning by businesses nearly impossible, and paralyzing commerce. This lagging business regulatory environment is typical. As socio-economist Robert Prechter points out, the Glass-Steagall Act, which separated banking and investment activities, was enacted in 1933 after the worst of the depression, only to be repealed in 1999. Its repeal helped to facilitate the Ponzi financing boom of the 2000s. Thus, changes in regulations only appear after the proverbial "horse is out of the barn", and do little except to inhibit business activity.

Thus, we believe that QE2 is an ill advised program that offers little prospect of boosting economic activity. If the program achieves success, any gains in economic activity will be for a very limited period of time with major risks that any short-term gain will be swamped by incalculably high costs in the future. These unknown, questionable experiments in monetary policy are being made to correct problems that are clearly of a non-monetary nature.

A Treasury Bond Market Bubble?

Over the past several months a number of articles have surfaced emphasizing the theme that the Treasury bond market is in a bubble. The implication of these articles is that yields are so low that they can only go higher, with the result of substantial capital loss to those owning the Treasury paper. It is true that psychology drives markets in the short run making anything possible, so rates may rise or fall, regardless of long-term fundamentals.

A bubble, however, refers to an asset with a price that is substantially beyond the asset’s fundamental or intrinsic value. This immediately raises the question as to what determines these values. A lucid description of this requirement is given by Dr. Seiji S. C. Steimetz in The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. In his article entitled "Bubbles", Dr. Steimetz defines the fundamental value of an asset as the present value of the stream of cash flows that its holder expects to receive, which includes the series of payments that the asset is expected to generate, and the expected price of the asset when it is sold.

Immediately, the Steimetz definition reveals a distinct delineation between stocks and bonds. The stream of cash flows for stocks, (i.e. dividends) is far less certain than the stream of semi-annual Treasury coupon payments guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the government of the largest economy in the world. In his article on asset bubbles Dr. Steinmetz gives no example of Treasury securities in a bubble, mentioning only common stocks and other types of assets. At maturity, the U.S. government also guarantees the par value of the Treasury bond. No such guarantee or maturity exists for commodities, real estate, common stock, or currencies in the hands of foreign holders.

Charles P. Kindleberger in his breakthrough book, Manias, Panics, and Crashes – A history of Financial Crises, is very explicit. He states, “ A mania involves increases in the prices of real estate or stocks or currency or a commodity in the present and near future that are not consistent with the prices of the same real estate or stocks in the distant future.” There is no mention of Treasury securities. Continuing, he adds “The term ‘bubble’ is a generic term for the increases in asset prices in the mania phase of the cycle.”

Determining Value For Treasuries

Investors are interested in the real or inflation adjusted present value of the stream of earnings from an asset, as well as the real value of the asset when it is sold. This is exactly the approach that Irving Fisher took in The Theory of Interest, published in 1930. According to the Fisher equation, one of the most tested and documented pillars of economics, the long risk-free yield (or the nominal yield) equals the real rate on long Treasury bonds plus the expected rate of inflation. Robert Loring Allen, in his 1993 biography on Fisher wrote: “Fisher’s theory of interest has assumed an honored position in the pantheon of explanations of the formation of interest rates, and indeed, in the functioning of the whole economy. No serious discussion of capital and interest can occur without considering it. If anything, over the years it has grown in importance.”

The real rate is very volatile and not predictable over the short-run. However, it averaged 2.1% over the long run and is mean reverting. Over time the long Treasury bond yield moves in the direction of inflationary expectations. Inflationary expectations lag actual inflation by a considerable period of time, sometimes more than several years. In addition, inflation is a lagging indicator. If the low point in inflation is well down the road, as cyclical analysis would suggest, then the low in bond yields lies ahead. Long Treasuries thus have substantial fundamental or intrinsic value and do not meet the criteria of an asset in a bubble.

Currently, inflation is tracking at a 1% annual rate and the bond yield is around 3.7%. Thus, the real yield is 2.7%, or 60 basis points above the 140-year mean (Chart 4). If the real yield were considerably below the mean and took place in an environment in which inflation was in the process of moving higher, the intrinsic value of Treasury bonds could be questioned. The real yield has remained above the mean for the past three decades. Thus, the mathematical tendency of a mean reverting series, sans economic theory, shows that the risk is that the real yield is headed below the mean and it could remain there for an extended period. For the Treasury bond market to be on the verge of a bond bubble: 1) the real yield would have to immediately lose its mean reverting characteristics that have held since 1871; 2) inflation would need to switch to a leading from a lagging indicator; and 3) inflationary expectations would need to lead actual inflation. All are unlikely.

Based on the Fisher equation’s superior analytic approach for determining value in the bond market, investors are still able to purchase long-term Treasury securities at prices which do not yet reflect their positive long-run potential.

Van R. Hoisington

Lacy H. Hunt, Ph.D.

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Bond Market Crash of 2010

from Mad Hedge Fund Trader:

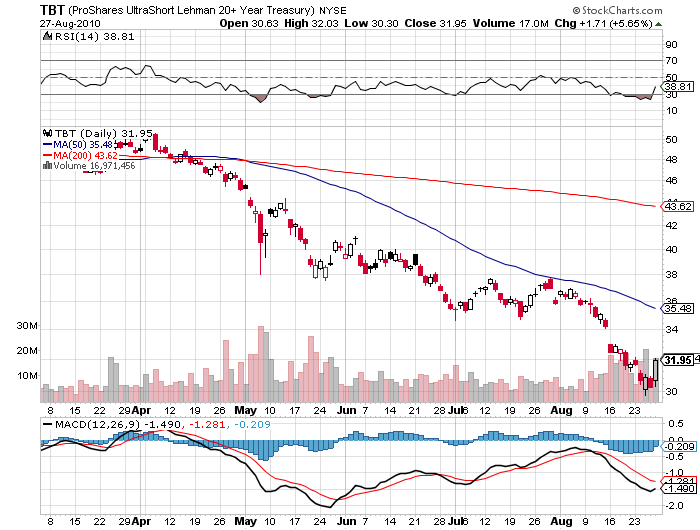

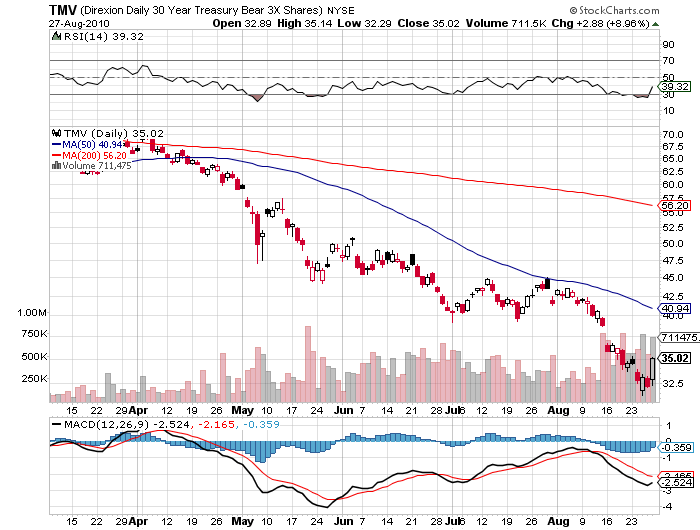

1) The Great Bond Market Crash of 2010. OK, maybe it hasn’t really crashed yet. But the two day, 3 ½ point sell off in the futures for the 30 year Treasury bond (TBT), at the end of last week was the sharpest drop in 18 months. Winston Churchill’s great 1942 quote, which marked the turning of the tide for Britain in WWII, comes to mind. “This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

In my recent piece on the extreme overvaluation of government debt, I pointed out that the last time rates were this low, Treasury bonds brought in a miserly 1.9% yield for a decade (click here for the piece). Professor Jeremy Siegel at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania has one upped me. After yields bottomed in 1956, bonds suffered negative returns for 30 years!

This should have occurred to me, as the first mortgage I took out on a Manhattan coop in 1982 carried an 18% interest rate. That was then Federal Reserve governor Paul Volker was waging a holy war on inflation and eventually won. I took out one of the first ever floating rate mortgages, and by the time I sold it three years later, the rate had melted down to only 11%. I tell this story to kids buying their first starter homes now and they look at me like I’m some kind of dinosaur.

I have always believed that markets will do whatever they have to do to screw the most people. A big part of the parabolic move in bond prices was caused by so many investors going into this the wrong way. Hedge funds were short Treasuries and long steepeners, while mutual and pension funds were underweight.

Remember, this was supposed to be the trade of the year? Of the decade? Only individuals and momentum players have been in there buying with both hands, not because they love low yielding bonds so much, but because they hate equities. All it took to set the cat among the pigeons was for Q2 GDP to come in at 1.6%, not as bad as expected, and for Ben Bernanke to remain silent about any plans to flood the markets with more liquidity.

This may not be the top in the bond market, but it is starting to resemble what tops look like. One more equity puke out in September could easily get us there.